Richard Wagner: the Prophet of the Iron Age

Richard und Cosima Wagner, Franz Liszt, 1880.

The prophet of the Iron Age

Imagination creates reality. The purpose of art: to make the unconscious conscious.

— Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner (1813-1883), a German composer known primarily for his operas (or as some of his later works became known, “musical dramas”), intended to redeem and reform a decadent mankind that, already during his lifetime, seemed to be heading towards a process of inevitable destruction. Wagner had one foot in modern times and the other in the world of the old Germanic heroes like Baldur and Siegfried; he became aware that with the passing of time, humanity had entered a kind of canyon of sleep so that former golden ages, in which man had enjoyed a magical relationship with the Universe, had been forgotten, the only evidence of such sublime conditions lying hidden in myths and legends in which nobody any longer believed.

With his artwork, Wagner offers liberation from the decadence of the Iron Age by silencing the madness of the modern world and opening our ears to the ancient voices from another world of another time, which today has been totally lost. In fact, the main strength of Richard Wagner's music lies in his ability to awaken the memory of the mythical Golden Age, the Homeland of true spiritual origin. Wagner saw himself as a prophet with a life destiny to “awaken the Germans to the grandeur of their blood ancestry”. He claimed that the Horn of Heimdall, guardian of the threshold between Gods and men, would one day sound its eerie call once more to herald the awakening of the Germanic Race from its deathlike slumbers.

All Wagnerian work turns out to be Gnostic, traditional, and initiatory. Thus, we are forced to “read between the lines”. Naturally, Wagner’s music is not for the masses; it is complex, extensive, deep and difficult to understand. The main emotional and spiritual force ―his driving force, so to speak― is the experience of entering the orchestra and the majesty of its immense choirs. The operas responded to the propensity for the overwhelming, sublime, romantic, tragic…. He resurrected all power and beauty of the German spirit with its wonderful music. Christa Schroeder recalled her saying that “Wagner's musical language sounded in his ear as a revelation of the divine.”

Wagner’s operas serves as a vehicle to awaken certain psychic subconscious energies through the musical sounds of the orchestra. Once that energy was released, Wagner hoped that, among other things, it would allow a more complete and accurate understanding of the complex political, social, cultural and economic problems of Germany and Europe, as well the entire world. Wagner proposed creating a true “new man” ―a “superhuman” in the manner of Friedrich Nietzsche― that is, a superior man in his experiences, his feelings, and his relationship with himself, society and the cosmos; in short, unleash the spiritual forces of the collective unconscious.

Gesamtkunstwerk

Parsifal stage in Wagner's Opera, by J Walker McSpadden.

Richard Wagner created the entirety of his artwork since he composed the music, orchestrated the scores and wrote the librettos in which he reflected his deep philosophical, psychological and initiatory knowledge. As an artist of staggering talent and imagination, he attempted “to combine the verse of a Shakespeare with the music of a Beethoven”. He sought to synthesize the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic complexity through his concept of “Gesamtkunstwerk” that is, the total and integral work of art, which sought to generate profound emotional changes in the audience's psyche. To use his own words, he intended “to artistically transmit my objectives to the emotional understanding ―not to the intellect― of the spectators”.

This phenomenon, however, does not operate on all men, but on a certain quality of the person who carries within himself the sensitivity and intuition to penetrate and understand the magnificent ideas and emotions that Wagner communicates. Carl Jung indicates that “the right method on the wrong man does not work.” Wagner himself considered whether such atrophy of spirit-vision in the general audience could be related to the gradual emergence and dominion of materialistic thinking. The final opera of the “Ring” entitled Twilight of the Gods (Gotterdammerung) dramatizes how the greed for gold sends Valhalla itself into oblivion in flames of desolation following the tremendous bloodcurdling battle of Gods and men. He compared the greed in his Twilight of the Gods to the “tragedy of modern capitalism and the spirit of Yiddish usury” which he claimed was threatening to destroy the soul of the German people.

Wagner's compositions are noted for the intensive use of Leitmotiv, musical themes associated with archetypes. The archetypes are innate psychic predispositions inside the mind that are projected onto the world to give it meaning and substance. Jung’s archetypes (the anima, animus, god, destiny, time, death, and shadow) repeatedly appear in the characters, situations, and leitmotifs throughout Wagner’s artworks. According to modern psychology, dreams contain symbols that find their expression in metaphors and projections in our conscious life. Wagner himself had powerful dream-like experiences that marked him deeply and were a key influence in his operas. While he was working on the score of Das Rheingold, for example, he dreamed a piece of music. Once he woke up, he would quickly turn it into the overture.

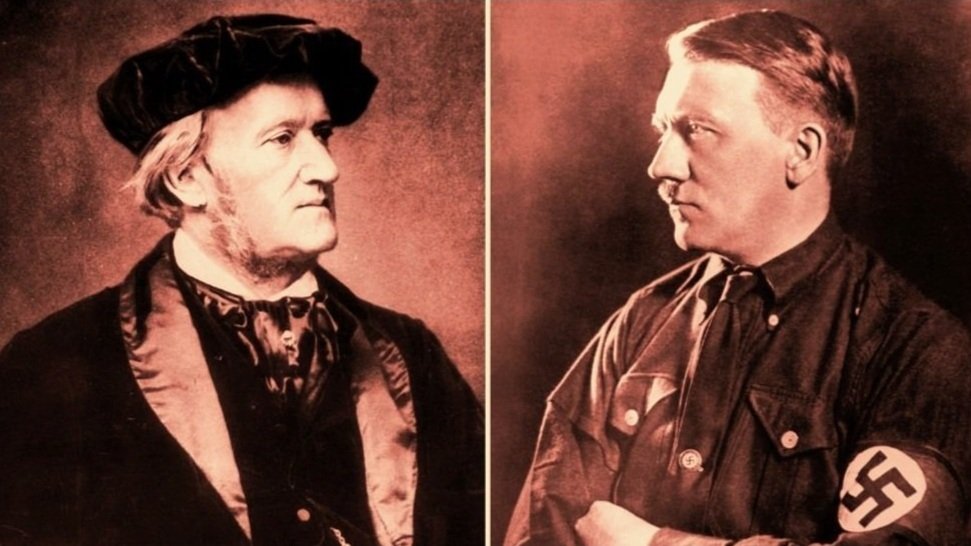

Adolf Hitler & Wagner

Richard Wagner & Adolf Hitler.

While Schopenhauer destroyed the meaning of values and Nietzsche proclaimed the need to go beyond them, Wagner provided a new set to replace the old. These three men, recognized more posthumously than during their lifetimes, defied the world and became, in time, Adolf Hitler's favorites. It is assumed that Hitler was drawn to Wagner's works because of their Norse myths and Germanic legends; their lone heroes and dark villains; feeling identified with Lohengrin, Siegmund, Siegfried, Wotan, Parsifal and any other Wagnerian character.

Wagner's operas had an almost religious effect on Hitler, even from his youth. Wagner’s first major opera, Rienzi, anticipated aspects of Hitler’s later history: mass politics, propaganda, and the relationship between a revolutionary leader (Führer) and his people. In Rienzi, however, Wagner criticized the revolutionary phenomenon he conceived, the tragedy of a charismatic leader and a popular redeemer.

We thus come to the key point in the “Wagner polemic”, which centers on the great admiration that Hitler professed for him and his artwork. The influence that Wagner exerted on Hitler was decisive in the ideological establishment of the future German Führer, the National Socialist party and the SS. Some ideas that inspired the SS were, for example, the recreation of Wagnerian spirituality, Nietzschean values, Prussian military virtue and medieval chivalric mysticism. Many of Wagner's work symbols were embodied in countless rallies, parades, marches, names of combat divisions, military plans, nationalist phrases, and slogans. Der Ring des Nibelungen, an opera loaded with strong nationalist traits, was the reason the city of Nuremberg became the Mecca of National Socialism, operating as a strong magnet on the collective psychology of the Germans.

Wagner and Hitler have been inextricably identified with the German nationalism, racism and anti-Semitism that today has a terrible image. It is not the intention of this article to deny it; Wagner was openly racist and anti-Semitic: “I regard the Jewish race as the born enemy of pure humanity and everything noble in it” (“Judaism in music”, 1850). However, let us remember that at that period, the Jewish people's social, political and economic influence was openly questioned in wide intellectual and cultural circles, both in Europe and the rest of the world. An example of this is made up of the racial writings of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who would become Wagner's son-in-law.

After WWII, Israel prohibits the performance of any work by Wagner in public, nor does it allow its transmission on radio and television.

The Twilight of the Gods

Ragnarok by Rasmus Berggreen.

Wagner's later dramas, Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal, are considered his greatest masterpieces. Der Ring des Nibelungen, known as the Ring cycle, is a set of four operas loosely based on figures and elements from Germanic mythology, in particular, the Old Norse Poetic Edda and the Volsunga saga. It is popularly known as “The Tetralogy”, alluding to its quaternary structure. Still, in truth, Wagner's drama forms a Trilogy with a prologue: The Valkyrie, Siegfried and Twilight of the Gods, preceded by an explanatory prologue, The Rhinegold.

Ultimately, Der Ring, like all of Richard Wagner's work, is nothing more than a metaphor for the eternal struggle between Good and Evil, be it in the physical world or in the soul of man. These forces are inseparable; the brighter the light, the sharper the shadows. That is the wisdom of the Ring opera; that uncovers the spiritual irreconcilability between Siegfried, the luminous hero Velsa, son of the god Wotan, and the dark and evil Nibelung dwarves.

The Ring of the Nibelung symbolically represents a process through which the original Golden Age was degraded and regressed until leading to the current Iron Age that precedes the Ragnarök or “twilight of the gods”, where the Wolf Fernir will open its jaws to devour all decadent, irretrievable and mortally wounded material creation. At the end of the Ring, the catastrophic fall and death of the gods unfolds, and the world ends up annihilated and consumed by fire and water.

Wagner understood that it had reached a point of no return; we are in a world that can no longer be saved or redeemed; it only seeds its own destruction. Ragnarök, the great Final Battle between Good and Evil, c is a masterful representation of the apocalyptic end that more and more people sense near. The current collective unconscious is tuning itself to activate an archetype of universal chaos, violence and destruction. We are heading towards a tragic End of History marked by blood and death.

Throughout the Twilight of the Gods, Wotan is permanently present, but only in the orchestra and the libretto, since he no longer appears on stage. Making a historical parallel, at the beginning of the year 1945, Hitler vanishes almost without a trace. It could well be that the Twilight of the gods has some parallel with the catastrophe that fell on Germany. But, following the same logic of this evolution, this destruction is necessary as a preliminary step for a new beginning in the cyclical time. Now we only need to await the arrival of Parsifal, the Avatar of the new Golden Age.

Parsifal

Parsifal, by Arthur Hacker. “Eternal life, as granted by the Grail, is only granted to those who are truly pure and noble!”

We can only understand Twilight of the Gods if we cover it together with Richard Wagner's latest work, Parsifal. It is not even an opera since the master composed it as a Bühnenweihfestspiel ”festival devoted to the stage” of Bayreuth. Parsifal is loosely based on Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival, the 13th-century epic poem by the Arthurian knight Percival. Although it has a plot suggested by elements of the Holy Grail legend, which coincides with the flowering of the Cathar Gnosis in medieval French, it also contains elements of Buddhist renunciation and compassion suggested by Schopenhauer's writings. Parsifal, the supreme work of Wagner, is one of those treasures that has been left for humanity, which like others, gives a physical form to universal wisdom.

Parsifal inspired the following interpretation of Hitler, which is probably quite close to Wagner's intentionality. For Hitler, what is celebrated in Wagner's ‘Parsifal’ is not the religion of piety; but the pure and noble blood, a blood whose the Grail’s brotherhood of initiates has sworn to protect. King Amfortas, to whom he was entrusted the custody of the Holy Grail and the Holy Spear, succumbs to the magic and sensual delights of a decaying civilization, falling into the arms of Kundry. Klingsor, the black magician, steals the Holy Spear and wounds him with it, causing a wound that never heals. Amfortas then suffers an incurable disease, the corruption of blood purity. In a vision, he describes how someone, a Chosen one, will come to save him: “Durch Mitleid Wissend, der reine Tor”: “Enlightened by compassion, the pure fool; wait for him, the one I choose.”

Amfortas can only be redeemed by Parsifal, the “pure fool”, able to overcome all trials and dangers, thanks to the purity of his heart. Parsifal defeats Klingsor, recovers the Spear and reaches the Grail Castle at the top of Montsalvat. By touching the wound of Amfortas with the tip of the Spear, the king is miraculously healed. Parsifal then climbs the altar steps, and takes the Grail from the sanctuary. According to Wagner, a white dove descends from the dome, a symbol of the “divine spirit”. Parsifal has conquered the two highest symbols of the initiatory power: the Holy Spear and the Grail ―symbols of undeniable sexual connotation― becoming the new Grail King, 'the anointed one' to restore the Golden Kingdom.

Nietzsche explains that his definitive break with Wagner occurred when he witnessed the premiere of Parsifal in Bayreuth in the summer of 1882. He believed that Wagner's last work represented a surrender to Christianity, which he attributed to the master's old age. He probably never penetrated the true meaning of Parsifal and was left with only superficial interpretation, leading him to reject the ritual metaphor of the first act and the Christian framework of the entire play. He did not understand it was a Gnostic-Cathar artwork, deeply anti-Catholic and anti-Protestant, just as Wagner himself was.

As an initiatory work, Parsifal is the embodiment of the Übermensch described by Nietzsche. It is perhaps the most beautiful work of Richard Wagner. Not only does it represent a new vision, attitude and feeling before the world, but it also becomes the longing redeemer of the Aryan people; ‘the coming man’, the promised return of the Grail King that will restore the Regal Function in Europe. Parsifal, as the new incarnation of an Avatar, will replace the worn and unhealthy Messianic archetype of Israel. It is the New ‘Chosen One’ to restore the New Millennial Golden Age.

The promised emperor sleeps in the depths of a Thuringian grotto for the Germans, awaiting the day when he will lead Germany at the head of all other peoples. “Then, the Reich that will last a thousand years will cover all of Europe”, as Eric Muraise underlines, “the legend of the sleeping emperor will acquire a new magnitude when it is based on the poetic transposition of the legend of the Grail (Grail), holy cup, whose revelation will purify and unite all the dismembered Europe”.